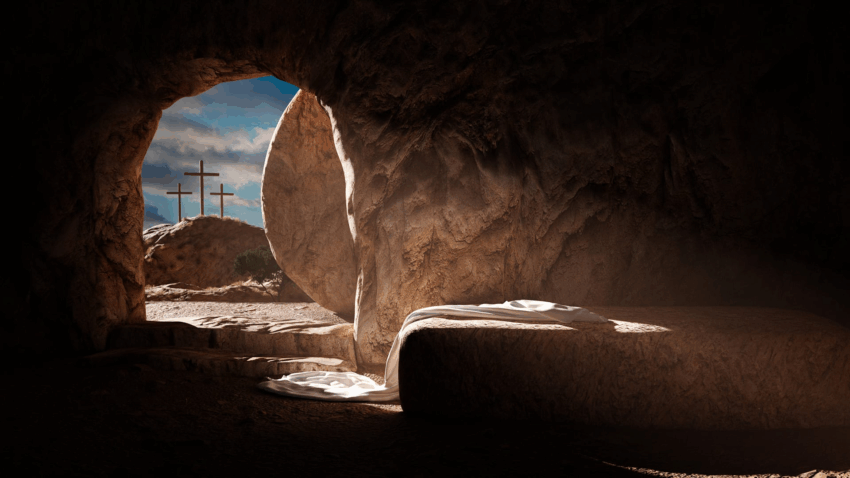

I delivered these remarks in church this Easter morning:

I’ve been thinking a lot about value and worth for a while, and I want to share some of my thoughts with you.

When we look at anything in the world, it will have many objective characteristics. It will be so high and so wide, it’ll weigh so much, it’ll be exactly this color, it will be made of exactly these materials. Those are all objectively measurable, and everyone who measures accurately will get the same result. But the worth of whatever it is… That’s fluid.

When I was young, I’d hear older people say that youngsters didn’t know the value of a dollar. Well, I did. One dollar equaled one comic book. Until it didn’t. Ten years ago, I could measure anything’s worth in terms of how many five-dollar Little Caesar’s pizzas I could buy instead. Until I couldn’t.

Gold is something we all think of having some inherent worth. So far in 2025, the price of gold per ounce has gone from $2600 to $3300. But does that mean that gold is more valuable, or that dollars are less valuable?

But here’s another question: If you were starving on a desert island, would you rather have an ounce of gold – a pound of gold – or an apple?

The more you think about value, the more you realize that value isn’t in the thing itself, like weight or color. Value is what is assigned to it by a person – someone decides how valuable whatever it is to that person. Everything, even gold, is valuable only to the degree that people want it. If nobody wanted it, it would be literally worthless.

But even the seller can’t decide how valuable something is to other people, not really. He may be able to set a price, but the person who purchases it really determines how valuable it is to that person. Something may be for sale, and one person will say, “I won’t buy it until it goes on special,” while another person says, “Shut up and take my money.”

If you want to see this principle in action, go to Ebay. Every auction on there is an example of different people placing different values on different things, many of which hold no value for you.

In fact, the whole idea of commerce and exchange relies on people assigning different values to a thing. The supermarket would rather have your three dollars than the gallon of milk. You would rather have the gallon of milk than the three dollars. If you both agreed on how to value the milk vs. the money, nothing would ever get sold.

Those of you who boiled and decorated eggs for Easter, you probably couldn’t help noticing that the price of eggs is almost twice as much as it was last year. And you might have complained, at least inside your head. But if you bought the eggs anyway, then you’re still saying that you’d rather have that dozen eggs than the four or five dollars.

In the simplest terms, how much you value something means what you would trade for it. And that value you assign can change rapidly. Ever had buyer’s remorse? It’s when you buy something – usually a big-ticket item – and immediately after the purchase is a done deal, you find yourself wishing you hadn’t bought it – maybe you should have bought something else, or just saved your money for longer. The value which you place on whatever you bought has very quickly and very literally changed to you.

Now, the idea of how much you value something meaning what you would trade for it… that doesn’t just apply to money.

We all have something that we trade for things and activities. Everyone has the same amount today, and no one knows how much of it we’ll end up having. I’m talking about time.

Have you ever thought about that? When you spend time on something, you literally spend time – you trade it for whatever you use that time for. Once it’s gone, it’s gone. And none of us know how much of it we have, only how fast we can spend it – twenty-four hours per day.

My father is an illustrator and graphic designer, and he says that the most offensive thing people ever say to him is, “Oh, I wish I could do what you can do.” His answer – which he doesn’t say out loud, because he’s a lot more polite than I am – is, “No, you don’t, because if you really wanted it, you would put in the years of studying and learning and practicing and failing and learning some more.” Those of you who play an instrument are used to hearing the same thing. No one is born being able to play the piano. It’s something you spend time to learn, and those who haven’t learned haven’t spent the time on it. What these people are saying is, “Gee, it would be great if I could have the result of spending time without actually spending the time, because it’s not worth that much to me.”

So. We’ve talked all about worth of all the things you buy and all the things you spend time on.

What is your worth?

There are two different ideas in the scriptures – in fact, they sound opposite. King Benjamin teaches us that God is not a good capitalist, because we don’t bring benefit to Him anywhere near what we cost. We’re a poor investment. This is from Mosiah 2:

I say unto you, my brethren, that if you should render all the thanks and praise which your whole soul has power to possess, to that God who has created you . . .

I say unto you that if ye should serve him who has created you from the beginning, and is preserving you from day to day, . . . if ye should serve him with all your whole souls yet ye would be unprofitable servants.

And behold, all that he requires of you is to keep his commandments; and he has promised you that if ye would keep his commandments ye should prosper in the land; and he never doth vary from that which he hath said; therefore, if ye do keep his commandments he doth bless you and prosper you.

And now, in the first place, he hath created you, and granted unto you your lives, for which ye are indebted unto him.

And secondly, he doth require that ye should do as he hath commanded you; for which if ye do, he doth immediately bless you; and therefore he hath paid you. And ye are still indebted unto him, and are, and will be, forever and ever; therefore, of what have ye to boast?

And now I ask, can ye say aught of yourselves? I answer you, Nay.

We don’t pull our weight. We don’t give back as much as He puts into us. We are always – eternally – in the red. King Benjamin says further,

Ye cannot say that ye are even as much as the dust of the earth; yet ye were created of the dust of the earth; but behold, it belongeth to him who created you.

But here’s the other idea idea, taught in the Doctrine & Covenants:

Remember the worth of souls is great in the sight of God;

For, behold, the Lord your Redeemer suffered death in the flesh; wherefore he suffered the pain of all men, that all men might repent and come unto him.

So how do we resolve this paradox? How can both ideas be true – that we are unprofitable servants, and that the worth of souls is great?

Now, did you notice that I just misquoted the Doctrine & Covenants?

It doesn’t say that “the worth of souls is great.” That would imply that worth is an inherent property. It says, “the worth of souls is great in the sight of God.” Worth is in the eyes of the purchaser. This is our worth in God’s system of values.

We established earlier that the worth of something is measured in what would be traded for it. What did God the Father and His son Jesus Christ trade for us?

You know the answer. John 3:16-17:

For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.

For God sent not his Son into the world to condemn the world; but that the world through him might be saved.

Or again from the Doctrine & Covenants, right after “the worth of souls is great in the sight of God:”

For, behold, the Lord your Redeemer suffered death in the flesh; wherefore he suffered the pain of all men, that all men might repent and come unto him.

On this Easter Sunday, we don’t just remember the “what” of what Jesus did, we remember the “why.” The incomprehensible love of the Father and the Son literally doing all that could possibly be done for us to return to Their presence and be truly happy.

So this answers the question about our worth. God values us – me, and you, and you, and you – infinitely. And outside of His love, we have no inherent value that we can boast in.

There’s a song by Janice Kapp Perry that people of a certain age will remember:

For I am of worth

Of infinite worth

My Saviour, Redeemer, loves me

But remember: Our Savior doesn’t love us because we’re of infinite worth. We are of infinite worth because the Savior loves us. Our worth is entirely in heavenly eyes. And I thank my God and my Savior for valuing me as He does.

Eh, God may not be a “good capitalist” in the sense of being a shrewd investor, but in terms of what capitalism itself by definition is? Bearing in mind that capitalism’s enemies are the very ones who coined the word, God is a very good capitalist; the various brands of socialists who’ve been trying to replace capitalism with any other system these last few centuries were always trying to come up with an enforceable alternative to its central tenet: any given item (product or service) is worth exactly what someone will give for it, no more and no less. Considering what God gave in exchange for us, that makes us very valuable indeed… albeit only in His eyes, as you note; that no one else would ever pay that much is not particularly relevant, no matter how much capitalism’s detractors wish it were.

Of course, the way God assigns us this value is neither particularly fair nor economically shrewd, but that’s actually kind of the point our Messiah made in at least three parables he told us: Matthew 20:1-16, Matthew 25:14-30, and Luke 19:11-27. We’re valuable because of what God gave (and will give) for us, not because we’ve ever had any inherent value that made this a “fair” price God could ever be compelled to pay. The King (or the landowner in that first parable) rewards his laborers (and punishes the slackers) as he sees fit, not as some worldly notions of “justice” or “fairness” demand.

Oddly enough, your conclusion reminds me of the end of the animated movie Batman Beyond: Return of the Joker, in which Bruce Wayne gently chides his successor Terry McGinniss for telling him (at the beginning of the movie) that he saw putting on the suit and taking up Batman’s crusade against crime as a way of redeeming himself for some of his earlier failings as a juvenile delinquent. “I’ve been thinking about something you once told me; and you were wrong. It’s not Batman that makes you worthwhile; it’s the other way around. Never tell yourself anything different.” Likewise, we don’t earn our value in God’s eyes by taking up various crusades and doing what is good and right, we take up those crusades and do what’s good and right because God loves and values us so much; getting this cause-and-effect relationship reversed in our doctrine is arguably the one easy heretical mistake to make that has brought more disaster to Christians down through the centuries than just about any other mistake we’ve ever made.

Yes, well – “capitalist” in the sense used elsewhere in my remarks, as an investor who gets more out of the system than he puts in.

Well, in Matthew 25:24-27 and Luke 19:20-23, the slackers in each of the parables seemed to take their master to be that kind of capitalist. (In each case, the master standing in for God neither affirms nor denies the assessment, basically saying “So—genius—if I’m the kind of guy who likes to exploit others for profit as you say, then why didn’t you use the money to get me something I could exploit!?”) Of course, the analogy breaks down in view of God owning the entire “system” (i.e. the universe) already; how can a guy with infinite wealth get any wealthier?

Such is the mystery at the foundation of our faith: “What’s in it for God? Why does He value us so highly?” The only honest answer we can give such questions is “No explanation is forthcoming. He just does.”