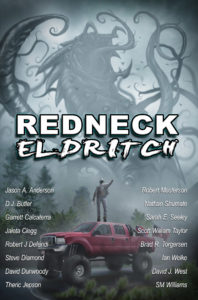

I am very proud (I think not inordinately) of my story, “Ostler Wallow,” which appears in REDNECK ELDRITCH published earlier this spring. I’m so proud, in fact, that I’m reproducing here the “sneak peek” posted this morning on the Cold Fusion Media website:

I am very proud (I think not inordinately) of my story, “Ostler Wallow,” which appears in REDNECK ELDRITCH published earlier this spring. I’m so proud, in fact, that I’m reproducing here the “sneak peek” posted this morning on the Cold Fusion Media website:

**********

I aint had the dream abowt the corners for long years. I didnt no I misst it. Wen I first had it over and over, way back in the bigining, the corners fritened me so bad I almost left the wallow and wats here. But now I no that the corner cuttin into you is the only way corners can embrase you.

The first I heard that the old bastard was dead, I was down at Roy Sadley’s store on a Tuesday morning; on top of the normal things Beth had sent me for, I needed a new mattock blade, as I’d sharpened the old one down to a nubbin I could shave with. Roy Sadley saw me come in, and the first thing he said was, “Phineas, your grandpap’s passed on.”

At first I thought he meant my grandfather Grandin, my mother’s father—he’s the only one I ever thought of as “my grandpap”—but that good man had already been been seven years in the Lutheran churchyard in Timoree. But Roy just went on.

“It was my Jude that found him,” he said. “We hadn’t seen Ephraim for a few weeks past when he said he’d be in, and I had stuff for him, so I sent Jude to truck it up to him in the Wallow, and that’s how he found him in the cabin.”

Ephraim. So that would be Ephraim Joel Ostler, my pap’s pap. I didn’t really know how Roy expected me to react, so I just shrugged.

“All gotta go sometime,” I said, just to be saying something.

“True ’bout most people,” Roy agreed, “though I ain’t sure I figured it applied to Ephraim. He’s still up there—Jude just barely got back, and he didn’t know what to do—so I guess you’ll want to go up there for him?”

I said, “Why?”

That took Roy back a step, and his bad eye rolled in surprise. “Well, he is your own blood kin—”

“I only set eyes on the old bastard three times in my life, and never spoke a word to him ever. I’m guessing if there’s someone who wants to take the effort to gather him and put him ’neath the dirt, they’re welcome to. I’ve got other things to do.”

Roy was so shocked that both his eyes looked straight at me, up and down. “You listen here, Phineas,” he said in a rough voice, “I don’t say you gotta make up and like him now that he’s passed, but there’s some family responsibilities you gotta take as the eldest, the man of the family. Obligations, even, no matter love nor hate.”

“So let my cousin Walter deal with it,” I said. “He’s older than me.”

Roy looked at me like I’d started speaking in tongues. “The oldest Ostler,” he said in a voice like you’d speak to an idiot child. “Walter can help with the funeral and the like, heck yes, but he’s a McKinnon. You’re the last Ostler, and that means something.”

I didn’t like the look in either of Roy’s eyes, so I glanced around the store to give myself a break from them. Sadley’s is a comfortably shadowy old store, with windows hazed over with dust and smoke so that sunlight coming through softens and blurs all around. There were a couple of old-timers by the small stove with the coffeepot, playing cards with a deck that I knew for a fact was missing the three of hearts. They kept their eyes on their cards and played right ahead, but I could tell all the same that they were both listening to Roy and me. Sadley’s hadn’t had a working radio since a tube blew in October, so there was nothing else to listen to.

“Fine,” I said. “I need sugar and coffee and a new mattock blade, and ring up an extra dime so I can use your phone to call Walter anyway.”

Roy’s face softened, and his bad eye went back to looking at whatever it wanted to. “Ain’t no need of that, Phineas,” he said. “You go right ahead and make the call.”

Sometims I feel like I got a therd eye in the back of my hed that dosnt see all the normal stuff that the Ssun shows becus it dont need lite to see by. It can see by the glow of the Edjes that are all around us, fillin the distans bitween all the things. The eye aint alwaz in back of my hed, somtimes its too the side or rite up top, but becus it dosnt see with lite it dosnt go blind with the Sun. And somtimes I dont no were it is, but it sees down, strate down, to all the things I love, and it sees so much it openss my Mouth and lets out all it sees in words and notwords til I got no breth left.

Most families around these parts have their own mountain or hill. When I say “have,” I don’t mean that they’ve got title to it, with fancy pieces of paper and something written in a book down at the county courthouse away in St. Stephen. Those families have been up here since before there was any county courthouse, or any St. Stephen, and we own what we own because we own it, not because a paper says.

Like I said, most families got a mountain or something. The Ostlers, we’ve got the Wallow.

It’s away west off the land we live on, right in the crotch made between Blair Mountain and the Godfrey Ridge, a low spot where the rain runs down and makes a huge soggy puddle with inlet and no outlet, always in damp shadow because the sun don’t shine there except right at midday. It’s like our own little swamp in the hills, with plenty of frogs but no fish because there’s no way for them to have gotten there. In the middle of the Wallow is a hump of black rock with moss growing up all sides, and on top of the rock is the hunting cabin put there by my great-great-great-grandfather Ostler.

That’s where old Ephraim Ostler, my grandpap, had lived since the night that he killed my grandmother and got driven out of the house—the same house I live in now—by my pap, Eliazar Joel Ostler, when he was all of thirteen years old.

I think I heared its Name in my dream last night, but it wasnt ear-hearin, I only heared it with somethin deep in the senter of my head, a part that almost doesnt no how to hear because it hasnt heared for so long, for ages and ages back throu Fathers and Sons. But I heared it with that somethin in my head, I heared its Name or mabe only part of it becose it felt like its hole Name wouda bin too big for my head to hold it in at onct. And becose it warnt ear-hearin, its nothin I can say with my maoth, but thats okay becose I dont think its somethin I have a right to say. Names is presious, and even the little bit I got is presious, and I am to keep it safe and presious.

Walter had a telephone in his house, and his wife Clara picked it up after two rings. Walter had grown up here in the hills but Aunt Rose had let him go away for school when he was fourteen, and he never really came back. He’d gone off to the war—he was in the Pacific, though he never saw any fighting—then went to university and came out a Doctor of Divinity. Now he lived down in St. Stephen and was the pastor of a Methodist church. Clara said he was out and she’d have him ring me back as soon as he got in, but I knew Beth would be wondering where I’d got off to if I stayed down at Sadley’s too long, so I told Clara the main points about old Ephraim’s being dead—main points being all that I knew myself—and told him to call back and talk to Roy if he wanted to help me clean him out the cabin in the next couple of days.

Roy was listening, and as I hung up, he said, “Don’t you think you oughtta go up there right away and collect him?”

While I’d been putting the call through, Roy had pulled everything on my shopping list to the front counter. I hoisted the bags up and balanced them on my hip.

“He’d dead already,” I said. “A day or two ain’t gonna make him any more or less dead, is it?” I pushed out the door without waiting for an answer. From what I’d been taught by my pap, anything short of leaving the old bastard to turn to bones by himself in the Wallow was more than he deserved…

**********

This is just one of the stories in the anthology Redneck Eldritch, available now!