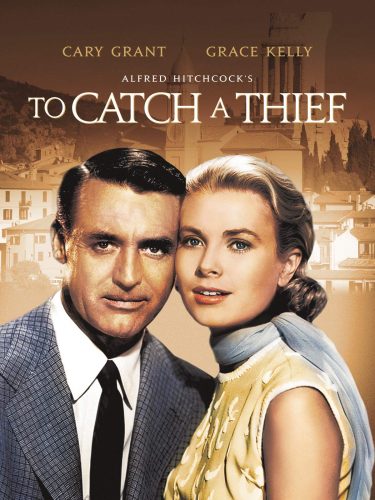

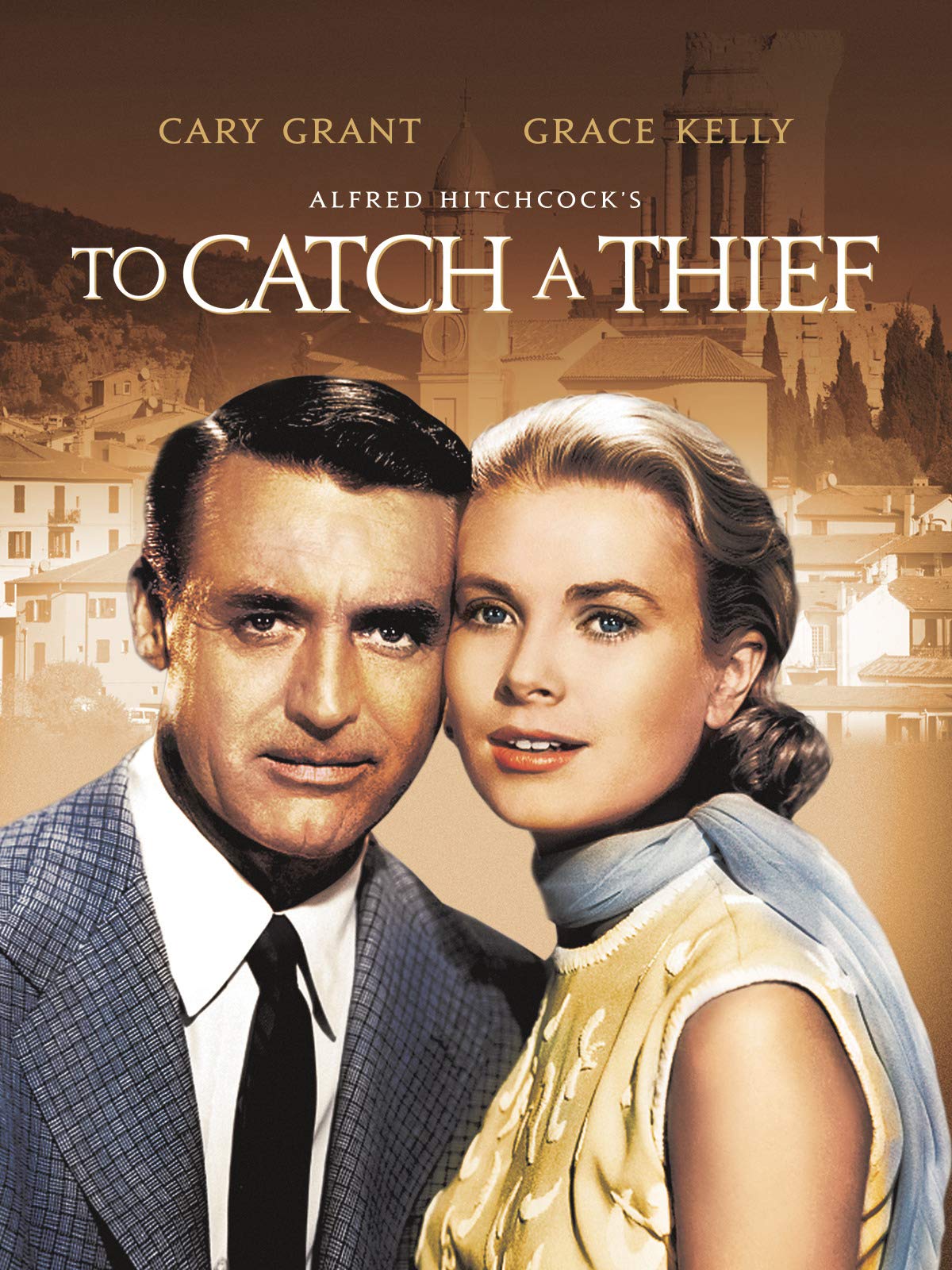

To Catch a Thief (1955) – What was it about Grace Kelly that persuaded directors to pair her with leading men old enough to be her father? The three roles I know her best for were in High Noon (1952), in which 23-year-old Kelly was the wife of 51-year-old Gary Cooper; Rear Window (1954), in which 25-year-old Kelly was the significant other to 46-year-old Jimmy Stewart, and this one, in which 26-year-old Kelly chases and is chased by a very tan 51-year-old Cary Grant. I mean, sure, being “elegant” makes you seem both mature and timeless — so much so that Kelly was four years younger than the actress playing the French “teenager” — but danged if it isn’t a more than a little squicky.

To Catch a Thief (1955) – What was it about Grace Kelly that persuaded directors to pair her with leading men old enough to be her father? The three roles I know her best for were in High Noon (1952), in which 23-year-old Kelly was the wife of 51-year-old Gary Cooper; Rear Window (1954), in which 25-year-old Kelly was the significant other to 46-year-old Jimmy Stewart, and this one, in which 26-year-old Kelly chases and is chased by a very tan 51-year-old Cary Grant. I mean, sure, being “elegant” makes you seem both mature and timeless — so much so that Kelly was four years younger than the actress playing the French “teenager” — but danged if it isn’t a more than a little squicky.

Anyway. Grant is a retired cat burglar on the French Riviera, who was paroled by the French for his compensatory work with the Resistance during the War. Now a new spate of jewel burglaries that ape his signature style has started, and if he doesn’t find who the real burglar is, the police will pin it on him. Kelly is a rich American heiress around whose neck such baubles sometimes hang.

I’m surprised that Grant didn’t die of skin cancer before filming was complete — I know that someone retired to the Riviera will get some sun, but he’s just so tan here. I can’t decide if that makes him look more active (and therefore younger), or more crinkly (and therefore older).

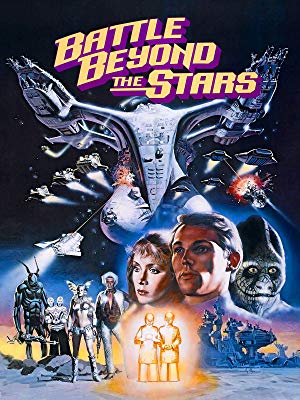

Battle Beyond the Stars (1980) – This Roger Corman-produced answer to Star Wars may be the most completely amortized movie production in the history of cinema. The spaceship footage was re-used wholesale in Space Raiders (see below), plus showed up in bits and pieces in at least ten other movies (including one that the IMDb hasn’t got listed). James Horner’s score was also completely re-used in Space Raiders and Wizards of the Lost Kingdom (1985). (I don’t know how Horner felt about that, but he didn’t have much room to talk as he plagiarized himself later, with his scores to both Star Trek II (1982) and Krull (1983) reusing an awful lot of BBtS‘s themes.)

Battle Beyond the Stars (1980) – This Roger Corman-produced answer to Star Wars may be the most completely amortized movie production in the history of cinema. The spaceship footage was re-used wholesale in Space Raiders (see below), plus showed up in bits and pieces in at least ten other movies (including one that the IMDb hasn’t got listed). James Horner’s score was also completely re-used in Space Raiders and Wizards of the Lost Kingdom (1985). (I don’t know how Horner felt about that, but he didn’t have much room to talk as he plagiarized himself later, with his scores to both Star Trek II (1982) and Krull (1983) reusing an awful lot of BBtS‘s themes.)

Oh, the movie itself? Pretty dire. It’s a variation on The Magnificent Seven (1960), as Richard “John-Boy Walton” Thomas gathers an assortment of mercenaries and fighters to defend his peaceful planet from John Saxon and his evil combover. The problem is that, unlike the focus in The Magnificent Seven being on the mercenaries and their relationships with the townpeople and each other, the focus here is on Thomas’ character, who’s whitebread and boring. The script seems like a first draft that was accidentally filmed.

Notable are the spaceship models, which are all pretty competent EXCEPT FOR the most prominent one, which Richard Thomas flies around to gather his mercenaries; it was designed by neophyte production guy James Cameron, and looks like a hammerhead shark with boobs.

Also notable — making up the only shining moments, really — is Robert Vaughn’s role as a master merc tired of being hunted by a galaxy of enemies. That’s right, it’s literally the same character he played in The Magnificent Seven.

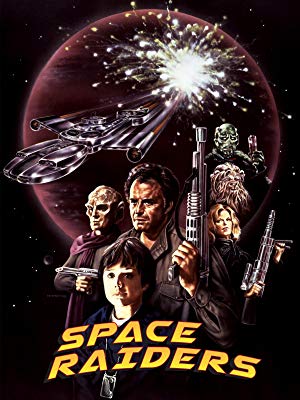

Space Raiders (1983) – I’d seen this before a couple of decades ago — I’d even written a review taking snide swipes at the child actor at the center of it, and gotten a bunch of pushback from someone who must have been his Aunt Edna — but I wanted to watch it again precisely because I’d just seen Battle Beyond the Stars, from which the space footage was taken.

Space Raiders (1983) – I’d seen this before a couple of decades ago — I’d even written a review taking snide swipes at the child actor at the center of it, and gotten a bunch of pushback from someone who must have been his Aunt Edna — but I wanted to watch it again precisely because I’d just seen Battle Beyond the Stars, from which the space footage was taken.

I gotta say that writer/director Howard Cohen, a pedigreed workhorse in Corman’s stable through the ’80s, did a good job of constructing a story entirely dissimilar to BBtS but which could use as much of that movie’s space footage as possible (including, unfortunately, the hammerhead shark with boobs). In fact, considering the limited resources with which Cohen was working… this might actually be a better movie than BBtS.

Not that it’s good. The main plot spring is that a cute but personality-less moppet accidentally stows away on a spaceship belonging to an overweight Han Solo wanna-be and his crew of misfits, and said Solo-Lite makes it his mission to get the kid back home before search parties kill him or other mercenaries knock him off to hold the kid for ransom. It’s a serviceable plot, but doesn’t lead to much except for homages to other, better movies.

Maybe the one feature in which Space Raiders outshines BBtS is in its humor — again, not exactly good, but nowhere near as painful as the fleeting attempts at comedy which show up unwanted in BBtS.

Abandoned movies: War of the Robots, The Shape of Things to Come.

I suspect part of the reason for pairing all those middle-aged men with Grace Kelly is that both in movies and on TV, it’s easier to make guys look younger than they really are than gals. To be sure, we’ve seen a fair number of twenty-something gals playing teenagers in shows like Buffy The Vampire Slayer, and 19-year-old Paula E. Sheppard managed to pass herself off fairly convincingly as the 13-year-old Alice Spages in Alice, Sweet Alice (1976), but none of that compares to Jack Wild managing to play a fifth-grade boy (i.e. no older than 11) in Melody (1971) when he was 18 and going on 19. I mean, can you imagine an 18-year-old girl playing a preteen?

With guys, it’s generally more difficult to tell what age they are so long as they have no visible facial hair, wrinkles, or male-pattern baldness, whereas with gals, it’s only possible to fudge their ages so much in either direction: for any girl character below thirteen, your best bet is to cast a child actress roughly the same age, since it’s nearly impossible to disguise the curves girls start getting when pubescent, whereas boys don’t get any visible curves throughout adolescence unless they work on developing their muscles. Any actress over thirty, even if she’s well-preserved, is going to have a hard time playing a twenty-something character, let alone a teenager, while any well-preserved actor over fifty (with, as mentioned, no visible facial hair, wrinkles, or male-pattern baldness) can fairly easily continue to pass himself off as a suave and experienced thirty-year-old in a movie when partnered with a fresh-faced twenty-something actress like Grace Kelly.

Biology has also always supported a bit of a double standard socially: since a gal’s most fertile years run from about 16 to 26, those are typically considered the ages at which she is most attractive, whereas a guy’s fertility is fairly steady from pubescence onward, and his virility stands a good chance of lasting into old age (albeit almost inevitably with some decline even among the very well-preserved). Since gals traditionally are called upon to start bearing and raising the next generation as soon as possible, while guys are traditionally tasked with building a career and bringing home the bacon before they can go hunting for a bride, most societies consider it rather natural for somewhat older guys who are well-established financially to have a mutual attraction to younger gals in their prime childbearing years.

Then too, in the 1950s, most people associated tanning with youthfulness; whereas nowadays, you and I and most everyone else associate it with being crinkled up like a prune.